This

article is more than 1

year old

Children’s prisons inflict unspeakable damage on inmates. Close them now

There is no nurturing or rehabilitation in these

institutions – just a shameful litany of death and abuse

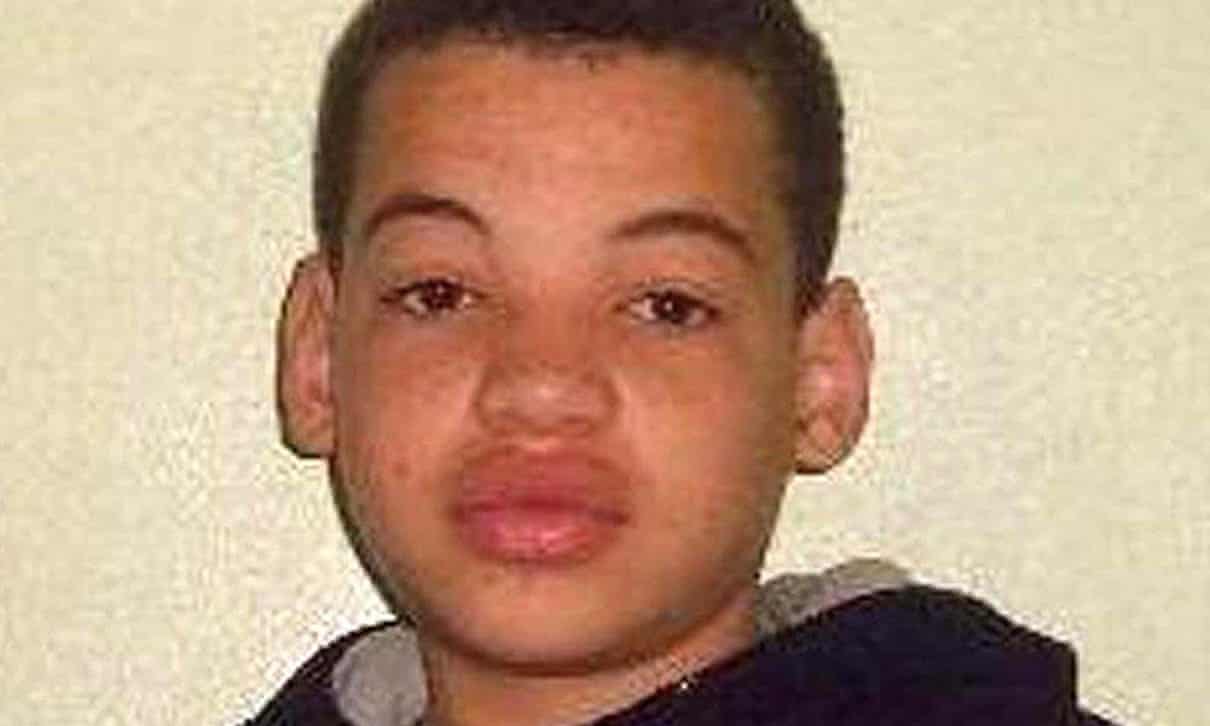

‘In

August 2004, 14-year-old Adam Rickwood became the youngest child to

die in custody in this country in over 100 years.’ Photograph:

Christopher Thurmond

Tue

23 Apr 2019 11.28 BST

T

he

15th anniversary of Gareth

Myett’s death

in a children’s prison is being commemorated by a campaign to end

child imprisonment in the UK. It is hugely appropriate – because in

the intervening years, those responsible for running children’s

prisons have repeatedly shown that they are incapable of nurturing

and rehabilitating the children in their care. Time and again we have

seen children leave these institutions abused and irreparably

damaged. That is, if they are lucky enough to come out at all. Gareth

Myatt wasn’t.

In

April 2004, Myatt died while being restrained by three custody

officers at Rainsbrook secure training centre near Rugby in

Warwickshire, operated then by G4S. The restraint followed his

refusal to clean a sandwich toaster. Gareth was under 5ft tall and

weighed six and a half stone. One of the restraining officers was 6ft

tall and weighed 16 stone. During the restraint Myatt said he could

not breathe. He was told: “If

you can talk, you can breathe.”

He died from positional asphyxia, choking on his own vomit. He was 15

years old and had been in custody for three days.

Article

39,

a children’s rights charity, Inquest,

which provides expertise on state-related deaths, the Howard

League for Penal Reform

and others launched

a campaign

in November to end child imprisonment. The campaign is pressing for

the closure of England’s child prisons, proposing that children are

only deprived of liberty as a last resort. It is also pushing for the

care and support of detained children to be moved from the Ministry

of Justice to children’s social care services.

This

might sound like a radical proposal, but it isn’t. In fact, in 1990

the UK signed up to the United

Nations Convention on

the Rights of the

Child,

which states that incarceration for children should only be used as a

measure of last resort and for the minimum time possible.

‘In

April 2004, Gareth Myatt died while being restrained by three male

custody officers at Rainsbrook secure training centre.’ Photograph:

Northamptonshire Police/PA

In

recent years, the numbers of jailed children has thankfully fallen,

but Britain

still locks up more children

and for longer than any other European country. And England, Wales

and Northern Ireland have the youngest age of criminal responsibility

in Europe – children can be convicted for a crime at the age of 10.

The most common age of criminal responsibility in Europe is 14.

Advertisement

We have

reported on child

detention in British prisons

for two decades, and have had the unwelcome privilege of “getting

to know” some of these children who died in prison.

There

was Joseph

Scholes,

who took his own life in Stoke Heath young offenders’ institution

in 2002. He had been sent there after taking part in a street robbery

in which a mobile phone was stolen. The prosecutor informed the judge

that Scholes had offered no physical violence to any person during

the offence.

In

sentencing, the judge acknowledged Scholes’s vulnerability and drew

the attention of the prison authorities to his acts of serious

self-harm leading up to his trial. Stoke Heath’s reaction? To place

him in a filthy strip cell with a concrete plinth for a bed, remove

his underwear and make him wear a rough garment that resembled a

horse blanket. At his inquest, a year later, some members of the jury

wept openly when they were passed the garment for inspection. Joseph

killed himself in that cell, nine days after he entered custody. He

was 16 years old.

We

have also repeatedly reported on the widespread physical and sexual

abuse of children in custody, stretching back decades and still

taking place now. In 2013, we

reported on the serial rape

of boys by a prison officer at Medomsley

detention

centre,

Durham, throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The perpetrator, Neville

Husband,

who ran the kitchens, was later sentenced to 10 years in prison and

is now dead. Many of his fellow officers appeared to turn a blind eye

to the horrors acted out before them. Giving evidence at Husband’s

trial, one officer said: “Husband always used to keep a boy behind

at night. We always felt sorry for that boy.” Sorrow, but no

action.

In

2014, we exposed

the abuse of children

in Medway secure

training centre,

then operated by G4S. In particular, we told the tale

of Roni Moss,

who was sent to Medway in 2010 when she was 15. She thought she may

have been pregnant and asked staff if she could have a scan. They

refused, saying she simply lacked iron.

Two

weeks later, she miscarried at around 2am. She rang the alarm bell in

her cell.

After

miscarrying in her cell, Roni Moss was given two sanitary towels and

told to go back to sleep. Photograph: Martin Godwin/The Guardian

“I

was in such pain, there was blood everywhere. I knew what was going

on, but I didn’t want to believe it,” she told the Guardian. The

member of staff took 25 minutes to bring three other officers into

her cell. “They gave me two sanitary towels and told me to go back

to sleep.” She was not taken to hospital for a week and a half. G4S

later confirmed to us that Moss’s account was accurate.

After

the Guardian report, Durham police launched Operation

Seabrook,

an investigation into abuse at Medomsley detention centre. In total,

1,784

people have now come forward

to allege they were victims of physical or sexual abuse at the

detention centre. This month, five former officers have been

convicted

of physical abuse at Medomsley

and jailed for a combined time of 17 years and 11 months.

Yes,

you may say, this is historical abuse that occurred nearly 50 years

ago. But, shockingly, these abuses are continuing today. In January,

we reported that staff at Medway secure training centre, now run by

the state after G4S was stripped of its contract, were still

unlawfully restraining children

for non-compliance. This week, parliament’s human rights committee

said the government must comply with international law and end use of

pain-inducing restraint techniques and solitary confinement of

children in detention.

Which

takes us back to another tragic death of a child in detention. In

August 2004, 14-year-old Adam

Rickwood

became the youngest child to die in custody in this country in over

100 years.

In

2004 Adam was remanded to Hassockfield secure training centre (built

on the site of Medomsley), where he had been remanded for a month on

wounding charges. At Hassockfield he was restrained for

non-compliance using a tactic called nose distraction technique which

basically involved a karate-like chop to the nose. Adam killed

himself shortly afterwards – but not before writing a detailed

letter asking, “What right do they have to hit a child?”

Fifteen

years on, we’re still asking the same question Adam did. And that

is why we support campaigners in calling for an end to child

imprisonment unless in exceptional circumstances. The simple truth is

the prison service and the private contractors have forfeited their

right to be trusted. Over the years they have shown that they only

know how to punish rather than repair our most damaged children, and

that is not good enough.

• This

article was amended on 24 April 2019. An earlier version incorrectly

indicated that Rainsbrook secure training centre is still operated by

G4S. That has been corrected. The location of Rainsbrook is more

accurately placed near Rugby in Warwickshire.

• Eric

Allison is the Guardian’s prisons correspondent. Simon Hattenstone

is a Guardian writer

News is under threat ...

… just when

we need it the most. Millions of readers around the world are

flocking to the Guardian in search of honest, authoritative,

fact-based reporting that can help them understand the biggest

challenge we have faced in our lifetime. But at this crucial moment,

news organisations are facing an unprecedented existential

challenge. As businesses everywhere feel the pinch, the advertising

revenue that has long helped sustain our journalism continues to

plummet. We need your help to fill the gap.

We believe every one of us deserves equal

access to quality news and measured explanation. So, unlike many

others, we made a different choice: to keep Guardian journalism open

for all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to

pay. This would not be possible without financial contributions from

our readers, who now support our work from 180 countries around the

world.

We have upheld our editorial independence in

the face of the disintegration of traditional media – with social

platforms giving rise to misinformation, the seemingly unstoppable

rise of big tech and independent voices being squashed by commercial

ownership. The Guardian’s independence means we can set our own

agenda and voice our own opinions. Our journalism is free from

commercial and political bias – never influenced by billionaire

owners or shareholders. This makes us different. It means we can

challenge the powerful without fear and give a voice to those less

heard.

Reader financial support has meant we can keep

investigating, disentangling and interrogating. It has protected our

independence, which has never been so critical. We are so grateful.

We need your

support so we can keep delivering quality journalism that’s open

and independent. And that is here for the long term. Every reader

contribution, however big or small, is so valuable.

Support

the Guardian from as little as CA$1 – and it only takes a minute.

Thank you.

Topics

No comments:

Post a Comment