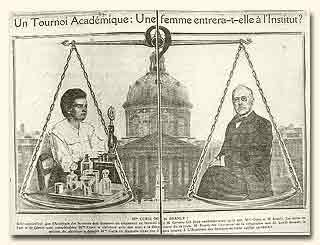

Her main rival for the seat was 66-year-old Edouard Branly, whose scientific reputation was based on his contribution to wireless telegraphy. When Italian Gugliemo Marconi was awarded the 1909 Nobel Prize for Physics for his work in that field, many French patriots felt stung by Branly's exclusion. |

|

Branly's claim to the Academy chair was also championed by many French Catholics, who knew that he had been singled out for honor by the Pope. For generations French politics had been bitterly divided between conservative Catholics and liberal freethinkers like Marie and her friends, and the split ran through every public action. Among the false rumors the right-wing press spread about Curie was that she was Jewish, not truly French, and thus undeserving of a seat in the French Academy. Although the liberal press came to her defense, the accusations did the intended damage. Branly won the election on January 23, 1911, by two votes. Curie responded to the snub characteristically, by throwing herself into her work. |

|

||

|

|||

|

“They can't comprehend at his house that he refuses magnificent situations...in private industry to dedicate himself to science,” wrote a friend of Langevin's. During the summer of 1911, as rumors about a relationship between Curie and Langevin began to spread, Madame Langevin began proceedings to bring about a legal separation. |

|

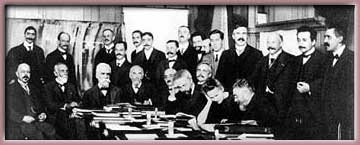

That autumn Curie,

Langevin, and some 20 other top physicists attended an international

conference in Brussels. While the scientists considered the challenge

to modern physics presented by the discovery of radioactivity, the

French press got hold of intimate letters that Curie and Langevin

had exchanged (or forgeries based on them).

|

On her return to

France, Curie discovered an angry mob congregated in front of her

home in Sceaux, terrorizing 14-year-old Ir�ne and 7-year-old Eve.

Curie and her daughters had to take refuge in the home of friends

in Paris. Meanwhile Langevin and a journalist who had reviled Marie

held a duel--an emotional but bloodless “affair of honor.”

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment